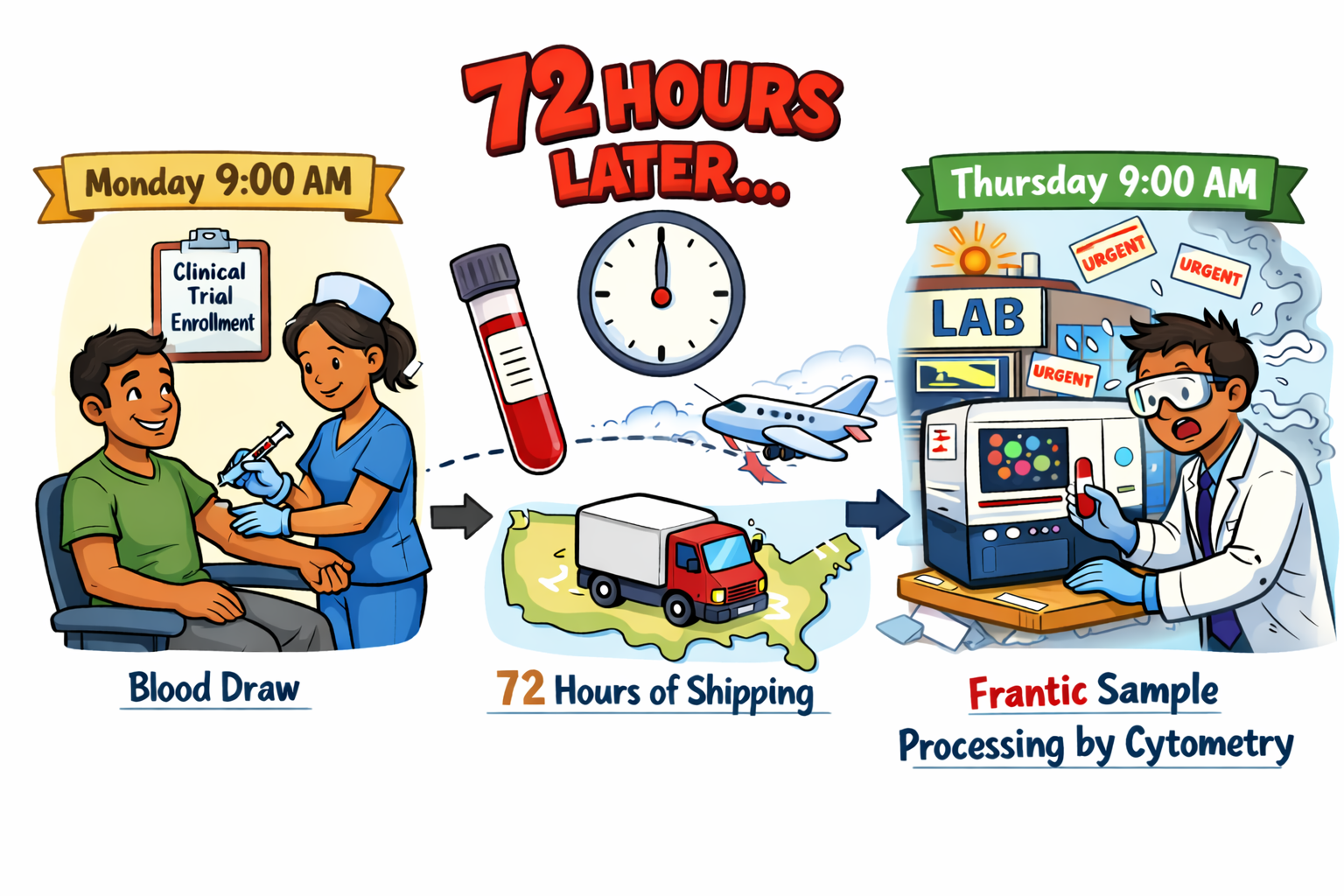

A patient enrolls in a clinical trial. A nurse draws blood at 9 AM on Monday. The sample ships to a lab across the country and arrives on Wednesday afternoon, 72 hours later. By the time a technician processes it, 49% of the immune cells are gone.

Approximately ~80% of clinical trial blood samples are processed 24 to 72 hours after collection due to transport to centralized laboratories, limited staffing, and scheduling constraints. At 72 hours, total leukocyte counts drop by nearly 50%. Monocytes by 88%. Neutrophils by 48%. Are cytometry results measuring drug effects, or changes caused by sample handling?

After a blood draw, immune cells no longer receive oxygen or metabolic support, and during shipping, samples experience temperature shifts and movement. These conditions reduce cell recovery in fresh whole blood. Delays longer than 8 hours (HANC-SOP recommendation for PBMC isolation) also change PBMC yield, subset frequencies, and detectable surface markers. And temperatures below 22°C reduce PBMC viability and functional readouts (Browne et al., 2024; Olson et al., 2011).

Degradation of blood samples starts within hours, with 15% cell loss by 24 hours. Two labs using identical instruments and protocols produce different results based on processing time alone. Samples processed at 24 hours no longer reflect the same immune cell frequencies and counts as samples processed within 2 hours.

What happens to immune cells as blood samples sit before processing

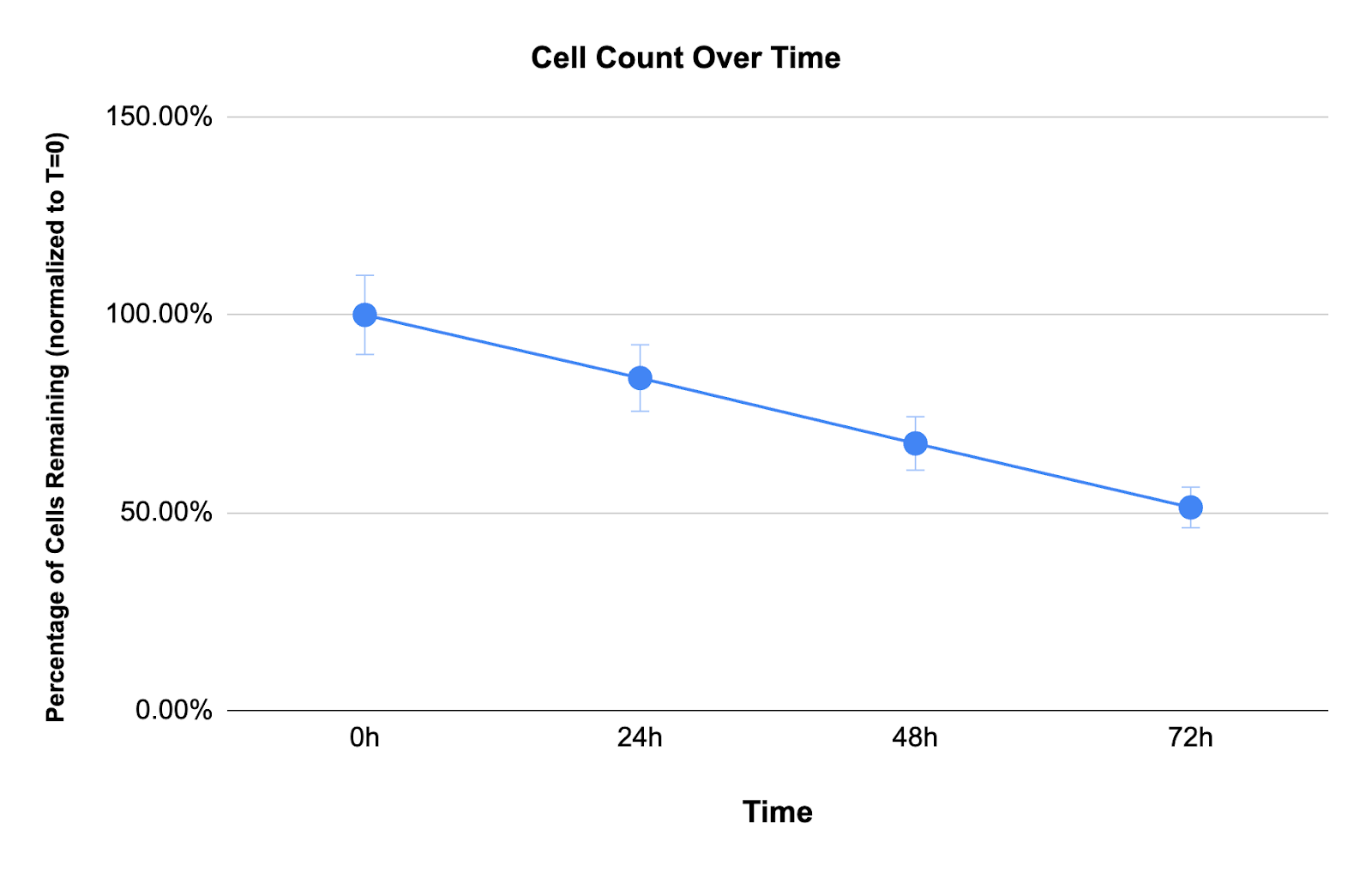

To understand how immune cells change over time, fresh whole blood was analyzed at 24, 48, and 72 hours after collection and compared to samples processed within 2 hours of blood draw.

Total cell loss increased with time:

- 24 hours: ~15% total cell loss

- 48 hours: ~33% total cell loss

- 72 hours: ~48% total cell loss

These losses accumulate silently. A "next-day" sample processed at 24 hours has already lost 15% of its immune cells before the researcher sees it. After three days, only half remain.

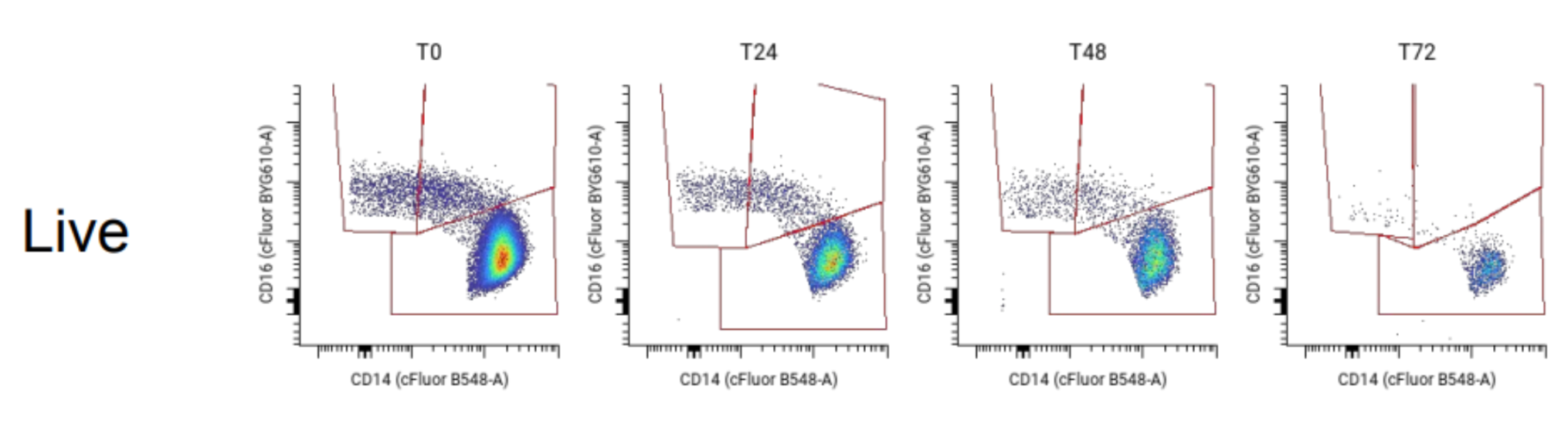

Immune cell loss differs by cell type, with the largest declines in monocytes

Cell loss was not uniform across lineages. In live samples processed at 72 hours, we measured:

- Total leukocytes: 49% decrease

- Neutrophils: 48% decrease

- Rare lymphocyte subsets: >25% frequency change by 51 hours

Monocytes, immune cells that respond to inflammation and help fight pathogens, essentially disappeared from samples at nearly twice the rate of other leukocytes. By 72 hours, monocyte counts dropped by 88% (Figure 2).

This uneven degradation distorts what trials are trying to measure. Imagine a drug that increases monocytes by 20%. If the sample sits for 72 hours before processing, monocytes will have declined by 87% from time-dependent cell death. The net result might show a decrease rather than an increase, leading researchers to conclude the drug failed when it worked.

Research on PBMC isolation confirms this pattern. Wang et al. (2016) reported 1% to 25% cell loss during processing, with an average of 14%. Temperature and timing affect which cells survive, changing the ratios between immune cell populations. Samples can pass quality control checks—acceptable viability, sufficient cell counts, clean data—while no longer reflecting what was actually in the patient's bloodstream.

Three approaches to sample handling

- PBMC isolation requires processing whole blood within 8 hours of collection. The isolated cells can then be frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored for years. This approach allows centralized batch analysis at any future timepoint and preserves samples for follow-up studies. The constraint is that 8-hour window: miss it and cell yields drop while the proportions of different cell types shift. For multicenter trials, this demands either on-site processing capabilities at every collection site or tightly coordinated sample transport.

- Fresh whole blood captures the immune system's state at the moment of blood draw. Unlike PBMC isolation, whole blood includes everything—neutrophils, granulocytes, and all lymphocyte subsets. But cells start dying immediately; by 72 hours, 49% of cells are gone. Trials shipping samples to centralized laboratories face a tradeoff: either process quickly (requiring distributed lab capacity) or accept substantial cell loss and compositional changes before analysis.

- Stabilized or fixed whole blood addresses the time problem by locking cells in place at collection. Fixation essentially stops degredation, keeping samples stable for days,months, or even years. This allows sites to collect samples on different days, ship them together, and analyze them as a batch—useful for multicenter trials where coordinating simultaneous processing is not possible. The tradeoff is that fixation can alter how surface and intracellular markers appear. Some markers get masked or change shape, preventing antibodies from binding properly. This means every cytometry panel used needs validation for fixed samples. Assays that work on fresh blood might need to be altered to work on fixed whole blood.

Choosing an approach based on what you need

Most blood samples are still processed live, with handling times ranging from 0 to 72 hours. This creates variability that becomes noise in the data. When fresh blood waits 72 hours before processing, 49% of leukocytes are lost, and monocytes decline by 90%.

Whole-blood fixation is becoming more common in multicenter trials as a way to control time-dependent loss. The method maintains population frequencies—the relative proportions of cell types—as long as the markers you need to measure survive fixation.

The right choice depends on three things: what the trial needs to measure (which cell types, which markers), what logistics are realistic (processing capacity at collection sites, shipping timelines), and how to standardize methods so results stay comparable across sites.

About Teiko

Teiko’s mission is to make cytometry simple.

Our integrated cytometry services — from sample preservation (TokuKit) to cytometry analysis (TokuProfile), rapid panel builds, and interactive data delivery (Dashboard) — enable teams to find critical immune insights fast that actually reflect patient biology and accelerate therapeutic development.

For more information, visit teiko-labs.com or contact us at teiko-labs.com/contact-us

.png)